Medieval studies can be defined in simplest terms as the study of Middle Ages Europe. But in the context of a liberal arts education, medieval studies is something much richer: a period of time in Europe that’s best understood through an interdisciplinary approach incorporating subjects like:

- Art history

- Archaeology

- Literature

- Linguistics

- History

- Cultural studies

- Women's studies

With a big-picture view through the melding of these fields, the definition of medieval studies becomes much more nuanced. It can be many things at once, defined by the lens through which you view it:

- Europe between the years 500 and 1500, bordered by the Emirate of Cordoba on the Iberian Peninsula in the West and by Eastern Orthodox Christians to the East.

- A concept invented by nationalists in the 18th and 19th centuries looking for an ideological glue to hold together newly-created states.

- An early model and precursor for 20th and 21st-century globalization.

- A combination of all these elements.

The Liberal Arts Introduce a Traditional View of the Medieval Period

The traditional definition of medieval studies is Europe over the millennium between the years 500 and 1500. 500 is a rough benchmark for both the widespread adoption of Christianity in the Roman Empire and also the decline of the Roman Empire. The year 1500 roughly coincides with all of the following:

- The successful Reconquista that defeated the Emirate of Cordoba in Spain

- The conquering of Constantinople by the Ottomans

- The Protestant Reformation

- The Renaissance

- The beginning of the Age of Discovery, the predecessor for European Colonialism

The popular perception of the Middle Ages can be summed up in one word: bleak. Medieval Europe invokes decline, outbreaks of the plague, superstitions, famines, invasions, and wars. It was a transitional period for Europe.

Through the Lens of Art History, We Get a Sense of this Bleakness of the Middle Ages

Germanic and Slavic tribes were invading from the east, followed centuries later by brutal Mongol conquerors. Vikings were coming from the north. Islamic invasions were pushing northwards from the southwest, and Ottoman Empire incursions were encroaching from the southeast.

Germanic and Slavic tribes were invading from the east, followed centuries later by brutal Mongol conquerors. Vikings were coming from the north. Islamic invasions were pushing northwards from the southwest, and Ottoman Empire incursions were encroaching from the southeast.

Through the lens of art history, we can get a sense of this bleakness from creative depictions during the Middle Ages:

Bloody and brutal depictions of Jesus being crucified:

- Christ of Mercy between the Prophets David and Jeremiah, painting by Diego de la Cruz (late 15th century)

- The Crucifixion, painting by Pietro Lorenzetti (1340s)

- The Crucifixion, mosaic by unknown artist in Saint Mark’s Basilica, Venice (1200s)

Depictions of brutal torture and pestilence:

- Codex Balduini Trevirensis, artist unknown, (1300s)

- The Martyrdom of St Apollonia, painting by Jean Fouquet (mid-1400s)

- Menologion of Basil II, painting by unknown artist (900s to 1000s)

- The Black Death, from the English School, Bridgeman Art Library (1348)

Art from the Middle Ages paints a clear picture of suffering. With science and medicine in their infancy, it’s no surprise that Middle Ages art also emphasizes Christianity, an optimistic answer to the disease, brutality, starvation, and wars that were endemic throughout medieval Europe.

A snapshot of history through medieval art is possible when viewing medieval studies with a broad liberal arts perspective. However, this wouldn’t stop opportunist 18th and 19th century nationalists from trying to co-opt Middle Ages Europe for their own agenda.

Medieval Studies as an Inquiry into Misogyny, Women’s Rights, and Superstition

The uncertainty and desperation that marked the Middle Ages is exemplified by the increase in witch burning during this time. Four out of five people killed for being witches were women, and most were over the age of 40. That’s at a time when the average life expectancy for a woman was around 44 years.

The uncertainty and desperation that marked the Middle Ages is exemplified by the increase in witch burning during this time. Four out of five people killed for being witches were women, and most were over the age of 40. That’s at a time when the average life expectancy for a woman was around 44 years.

Desperate times required desperate measures. The Middle Ages Church explained that bad harvests and disease were a result of sinners not pleasing God. But even despite exemplary demonstrations of piety, starvation and disease persisted. Many turned to whatever else was available: folk remedies and superstitions.

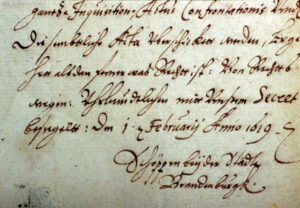

The Church viewed these as a threat to its power in addition to inviting God’s wrath and, as well as for political reasons, supported various inquisitions throughout Europe. These inquisitions – mobs of frightened villagers who had the Church’s blessing, as well as opportunists– were the first wholesale organized events that targeted older women as witches.

The Church’s persecution of witches led to the formalized Malleus Maleficarum, written by a clergyman. He used misogynistic stereotypes of women to put a religious and ostensibly logical spin on why women should be targeted and suspected of witchcraft.

Viewing medieval studies through the lenses of women’s rights and cultural superstitious beliefs offers a classic liberal arts perspective and sheds new light on how women have struggled for equity through the ages.

Medieval Studies Itself Has a Fascinating History

The Renaissance came to Europe to mark the end of the Middle Ages, and would eventually set the stage for nationalism. By the 19th century it had taken Europe by storm. Nationalist leaders needed a way to unite people and they realized that constructing a national identity based on ethnic and cultural heritage was a way of doing this. In Germany this marked a turning point for medieval studies that would affect the entire academic field.

The Renaissance came to Europe to mark the end of the Middle Ages, and would eventually set the stage for nationalism. By the 19th century it had taken Europe by storm. Nationalist leaders needed a way to unite people and they realized that constructing a national identity based on ethnic and cultural heritage was a way of doing this. In Germany this marked a turning point for medieval studies that would affect the entire academic field.

Under Wilhelm the First, Germany’s 300-plus kingdoms were unified into one nation with 26 states. The new country needed a nationalist narrative to glue it together, so at this time medieval studies was infused with new nationalistic energy, funding, and a domineering cultural zeitgeist.

Medieval studies became a way to promote the nationalist narrative in telling the story of Middle Ages Europe.

A flurry of scholarly Middle Ages research and study ensued and the field enjoyed its own Renaissance, which peaked during the time of Wilhelm the First and marked the crescendo of Europe’s age of romantic nationalism.

Middle Ages historiography (the study of historical writing) plays an important role in our understanding of how and why the field of medieval studies developed. A broad liberal arts view is vital for recognizing the influence of outside cultural and political forces in the field, and teaches an important lesson about history and who writes it.

Neo-Medievalism – A Modern Take on Medieval Studies

Because ideas from medieval studies had been co-opted so much by European nationalists during World War Two, after the war enthusiasm for the subject was at an all-time low.

Because ideas from medieval studies had been co-opted so much by European nationalists during World War Two, after the war enthusiasm for the subject was at an all-time low.

However, it would soon recover as an academic subject, and today in the age of globalization medieval studies is busy charting a new academic branch.

Neo-medievalism argues that medieval Europe provides an early template for globalization. It sees parallels between the formation of Europe in the Middle Ages and today’s globalized world:

- The Middle Ages template was that of a common religion, cultural homogeny, inter-connected trade, and decreased monarchical power.

- Today, globalization is providing a template where humanity has a common set of values, human rights and a humanistic sense of the common good. At the same time, the world is becoming interconnected by trade and the power of the state is being reduced by large multi-national corporations.

Today, medieval studies intersects with foundational liberal arts topics like ethnicity, global capitalism, religion, history… and the study of modern government, commerce and the phenomenon of globalization.